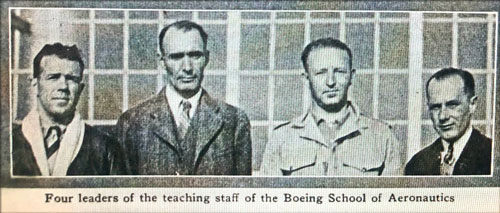

Leroy Burton Gregg (1896-1973) – aviator, instructor, and airport executive (with a nod to aviatrix Ya Ching Lee)

As a flight instructor at the Palo Alto School of Aviation, Leroy Gregg signed the Oakland Register 15 times from July 3 to September 14, 1929, using four different aircraft. An image of these aircraft is available from Stanford University’s Daily archives. After leaving Palo Alto, he would have a long presence in Oakland as an instructor at the Boeing School of Aeronautics and Captain for United Airlines from December 1929 to the early 1940s.

As a flight instructor at the Palo Alto School of Aviation, Leroy Gregg signed the Oakland Register 15 times from July 3 to September 14, 1929, using four different aircraft. An image of these aircraft is available from Stanford University’s Daily archives. After leaving Palo Alto, he would have a long presence in Oakland as an instructor at the Boeing School of Aeronautics and Captain for United Airlines from December 1929 to the early 1940s.

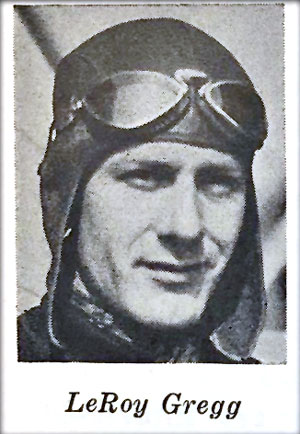

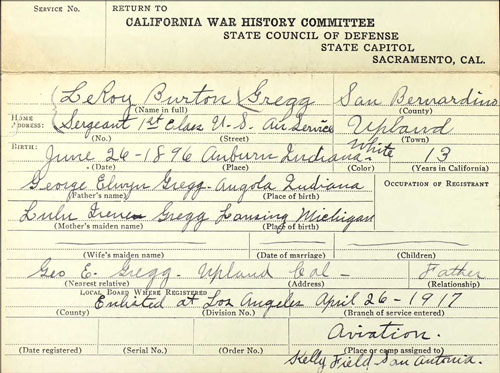

Mr. Gregg started flying at Cicero Field in Chicago in 1914, entered the U.S. Army in 1917 as a flying instructor, and served as a First Sergeant during World War I assigned to Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas. Mr. Gregg left the Army in 1920 to enter commercial flying and to teach flying as a reserve officer at Rockwell Air Depot in San Diego until 1927.

Mr. Gregg started flying at Cicero Field in Chicago in 1914, entered the U.S. Army in 1917 as a flying instructor, and served as a First Sergeant during World War I assigned to Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas. Mr. Gregg left the Army in 1920 to enter commercial flying and to teach flying as a reserve officer at Rockwell Air Depot in San Diego until 1927.

Born in Indiana in 1896 to a cigar maker, Mr. Gregg, an only child, moved with his parents from Indiana to Upland, CA in San Bernardino County around 1910. On April 2, 1919, Mr. Gregg married Mildred Gilbert. In 1928 they lived in southern California where Mr. Gregg was a test pilot for the Prudden Aircraft Company for a year and a half. After the start of the Great Depression, Mr. Gregg became a flight instructor at the Galt Technical Junior College of Aeronautics.  During this time, Mr. Gregg addressed members of Ontario’s Twenty-Thirty Club regarding new federal aviation regulations to go into effect July 1, 1929, requiring airport ratings and more stringent requirements for airplanes, pilots, and mechanics. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Gregg left southern California for the Palo Alto School of Aviation. Curiously, there’s no record of Mr. Gregg having worked at the Palo Alto School of Aviation except for a very brief mention in the October 1, 1929 Stanford Daily, and the flights recorded in the Oakland pilot register.

During this time, Mr. Gregg addressed members of Ontario’s Twenty-Thirty Club regarding new federal aviation regulations to go into effect July 1, 1929, requiring airport ratings and more stringent requirements for airplanes, pilots, and mechanics. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Gregg left southern California for the Palo Alto School of Aviation. Curiously, there’s no record of Mr. Gregg having worked at the Palo Alto School of Aviation except for a very brief mention in the October 1, 1929 Stanford Daily, and the flights recorded in the Oakland pilot register.

Mr. Gregg was notable for his thousands of hours of flying time and student instruction without incident. Unfortunately, he had a front-row (top-down?) seat to the first fatality at the Oakland Airport from a plane crash on August 12, 1930. While instructing a young woman in the air they witnessed a new pilot’s “nose-high” turn (the motor is at an angle slightly higher than the rest of the plane) causing it to go into a spin and drop from 400 feet.

Despite his safety record, he did take risks including imposing abnormal strains on a Boeing light craft by performing an outside loop (flying in a circle creating negative gravitational forces so one is being pulled out of, rather than pushed down into, the seat) to demonstrate the plane’s stamina. His lack of mishaps would eventually change although no accidents were fatal.

One famous mishap involves a 25-year-old aviatrix named Ya Ching Lee, America’s only woman pilot of Chinese descent. Mr. Gregg was teaching Ms. Lee acrobatics above the Oakland Airport in May 1935 when she was thrown out of the plane he was piloting due to a loose safety belt when the plane went upside down. Ms. Lee parachuted safely to San Francisco Bay. Mr. Gregg dropped a life preserver, and the U.S. Navy, stationed at the Oakland Airport, landed their amphibian plane (capable of taking off and landing on solid ground and water) in the shoal areas of San Francisco Bay. After being saved by a parachute landing, Ms. Lee was invited to join the Caterpillar Club, and Mr. Gregg’s parents, still living in Upland, CA., were showered with congratulations over the thrilling rescue.

One famous mishap involves a 25-year-old aviatrix named Ya Ching Lee, America’s only woman pilot of Chinese descent. Mr. Gregg was teaching Ms. Lee acrobatics above the Oakland Airport in May 1935 when she was thrown out of the plane he was piloting due to a loose safety belt when the plane went upside down. Ms. Lee parachuted safely to San Francisco Bay. Mr. Gregg dropped a life preserver, and the U.S. Navy, stationed at the Oakland Airport, landed their amphibian plane (capable of taking off and landing on solid ground and water) in the shoal areas of San Francisco Bay. After being saved by a parachute landing, Ms. Lee was invited to join the Caterpillar Club, and Mr. Gregg’s parents, still living in Upland, CA., were showered with congratulations over the thrilling rescue.

Mr. Gregg’s own crash occurred in November 1937 when his training plane motor cut out at 50 feet. The plane landed in the mudflats of San Francisco Bay causing some damage to the plane, but not to Mr. Gregg.

By 1939 the Boeing School was at capacity with 250 students from 38 states and 7 foreign countries. Students were required to be between 18 and 35 years of age with 26 being the maximum age for pilot instruction. Instruction was provided in four areas: flying, technical training, mechanics, and administration. As a flight instructor supervisor, Mr. Gregg published an article in Flying Magazine in 1941 entitled “Fledglings’ Timetable” about the advantages of following a rigorous training schedule. After peaking in 1942 to meet the demands of World War II, the Boeing School of Aeronautics closed in 1945.

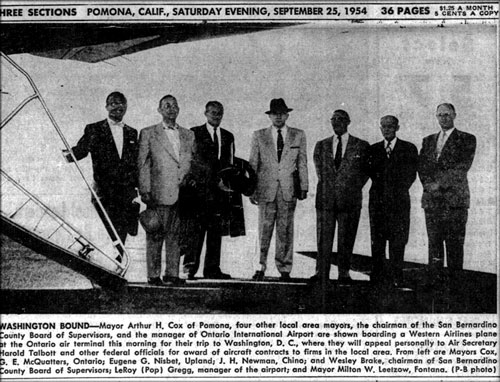

By the late 1940s, Mr. Gregg was working at Ontario International Airport in southern California. Rapidly growing from a 0.5-acre vineyard tract, the Ontario Airport was the base for plants such as Lockheed Service Corporation, Northrop, Douglas, and Southern California Aircraft Corporation with commercial flights offered by Western Air Lines, Pacific Air Lines, and others. After securing $500,000 in government funds to develop the airport including a new control tower, the Ontario City Council promoted Mr. Gregg to aviation director in 1953 with a salary of $800/month plus travel expenses.

Pleased with the airport’s growth, the Ontario City Council sent Leroy Gregg to Washington, D.C. in 1955 to seek a federal government contract for a tenant, Pacific Airmotive. The relationship soured; however, by 1957 when the Ontario City Council accused Mr. Gregg of not following their instruction and used the police to bar him from his office. Mr. Gregg sued the city for the $18,000 remaining in his $12,000/year three-year contract as well as $25,000 in punitive damages for malice and oppression. In the Superior Court trial, Mr. Gregg said he was ousted because of opposition to his ideas by a major aircraft tenant; the City countered with accusations of drunkenness and disloyalty. Two years after Mr. Gregg’s firing, the parties settled out of court in 1959 for $8,000. LeRoy Gregg died in southern California in June 1973 a few days after his 77th birthday.

Pleased with the airport’s growth, the Ontario City Council sent Leroy Gregg to Washington, D.C. in 1955 to seek a federal government contract for a tenant, Pacific Airmotive. The relationship soured; however, by 1957 when the Ontario City Council accused Mr. Gregg of not following their instruction and used the police to bar him from his office. Mr. Gregg sued the city for the $18,000 remaining in his $12,000/year three-year contract as well as $25,000 in punitive damages for malice and oppression. In the Superior Court trial, Mr. Gregg said he was ousted because of opposition to his ideas by a major aircraft tenant; the City countered with accusations of drunkenness and disloyalty. Two years after Mr. Gregg’s firing, the parties settled out of court in 1959 for $8,000. LeRoy Gregg died in southern California in June 1973 a few days after his 77th birthday.