Mildred Kauffman (1907-1932) - Aircraft Sales Pilot and Stunt Flier

A member of the newly formed women’s Ninety-Nines pilot club, a mechanic, and an employee of American Eagle Aircraft Corporation, 21-year-old Mildred Kauffman flew from Stockton to Oakland on November 22, 1929, with fellow pilots H.E. Trotter, American Eagle’s L.A. branch manager, and Claud Parker. Starting on the east coast in August 1929, these pilots were part of a 35,000-mile goodwill trip throughout the United States to promote aviation and American Eagle aircraft. Ms. Kauffman piloted an American Eagle Phaeton powered by a Wright J-5 165 horsepower 5 cylinder engine. The three-seater single-engine plane could hold two passengers side by side in the front with the pilot behind them in an open cockpit. Its cruising speed was 112 miles per hour, and with a 40-gallon gasoline tank, its cruising range was 430 miles at an altitude up to 16,000 feet[1].

A member of the newly formed women’s Ninety-Nines pilot club, a mechanic, and an employee of American Eagle Aircraft Corporation, 21-year-old Mildred Kauffman flew from Stockton to Oakland on November 22, 1929, with fellow pilots H.E. Trotter, American Eagle’s L.A. branch manager, and Claud Parker. Starting on the east coast in August 1929, these pilots were part of a 35,000-mile goodwill trip throughout the United States to promote aviation and American Eagle aircraft. Ms. Kauffman piloted an American Eagle Phaeton powered by a Wright J-5 165 horsepower 5 cylinder engine. The three-seater single-engine plane could hold two passengers side by side in the front with the pilot behind them in an open cockpit. Its cruising speed was 112 miles per hour, and with a 40-gallon gasoline tank, its cruising range was 430 miles at an altitude up to 16,000 feet[1].

American Eagle Aircraft Corporation, located in Kansas City, Missouri, designed and manufactured trainer aircraft in a price range of $3,200 to $8,000. The timing behind the goodwill tour was to promote American Eagle aircraft after it purchased the Wallace Aircraft Company in July 1929 resulting in American Eagle being the world’s third-largest aircraft production company. At the time, Kansas City was a hub for the nation’s airways being 24 hours from New York City and L.A. (American Eagle would fail financially due to the Depression in 1932, the same year as the demise of this pilot.)

Growing up with a love of airplanes, Ms. Kauffman sought out how to learn to fly and repair airplanes after graduating from Paseo High School in Kansas City. One of 34 women pilots out of a total of 5,200 licensed pilots, the goodwill tour afforded Ms. Kauffman sufficient hours to become the 16th woman pilot with a transport license. However, she was frustrated that American Eagle hired her only as a reserve pilot; she longed to be a regular pilot on a transport line. She is quoted in 1930 as saying: “The big companies are not going to hire women as passenger plane pilots, of course. Probably they never will, any more than a railroad would hire them as engineers or bus companies as drivers.”

Growing up with a love of airplanes, Ms. Kauffman sought out how to learn to fly and repair airplanes after graduating from Paseo High School in Kansas City. One of 34 women pilots out of a total of 5,200 licensed pilots, the goodwill tour afforded Ms. Kauffman sufficient hours to become the 16th woman pilot with a transport license. However, she was frustrated that American Eagle hired her only as a reserve pilot; she longed to be a regular pilot on a transport line. She is quoted in 1930 as saying: “The big companies are not going to hire women as passenger plane pilots, of course. Probably they never will, any more than a railroad would hire them as engineers or bus companies as drivers.”

Initially achieving fame on September 16, 1929, for winning the 25-mile women’s race at Kansas City’s nine-day International Air Circus and Pilots’ Reunion, Ms. Kauffman stayed in the news. In February 1930 Ms. Kauffman sought to exceed Mildred Stinaff’s 42 consecutive loop record in St. Louis. At an altitude of 8,400 feet, Ms. Kauffman reported making a total of 57 loops, but due to haze, officials on the ground were unable to see 11 of the loops establishing her world record at 46 loops. (Flying loops, one of several popular acrobatic maneuvers, consists of a 360-degree vertical turn where the pilot is upside down at the top of the loop.)

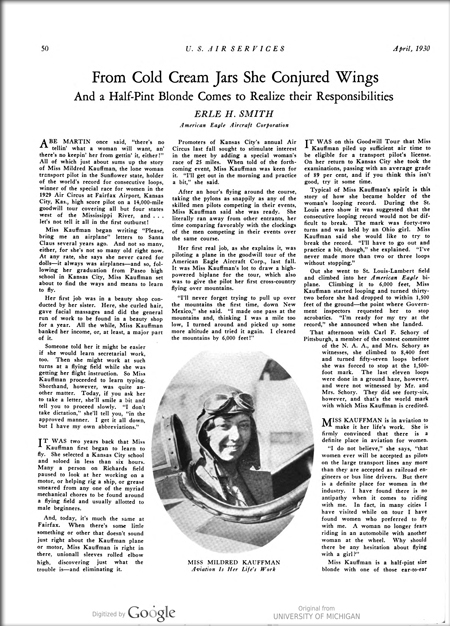

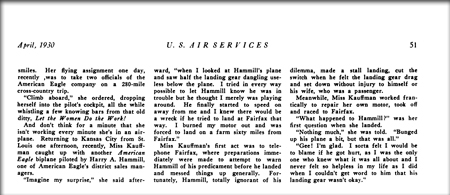

Within two months she attempted to break her loop record in Buffalo, but her plane stalled. Flying upside down she slipped from her safety belt and went over the side. Opening her parachute and landing safely in the soft mud outside the Buffalo Airport, Ms. Kauffman was the third woman granted entry into the Caterpillar Club, a club formed in 1922 whose members have all been saved by a parachute. American Eagle Aircraft Corporation capitalized on her fame by publishing an article about Ms. Kauffman in U.S. Air Services entitled “From Cold Cream Jars She Conjured Wings, And a Half-Pint Blonde Comes to Realize their Responsibilities.”

Within two months she attempted to break her loop record in Buffalo, but her plane stalled. Flying upside down she slipped from her safety belt and went over the side. Opening her parachute and landing safely in the soft mud outside the Buffalo Airport, Ms. Kauffman was the third woman granted entry into the Caterpillar Club, a club formed in 1922 whose members have all been saved by a parachute. American Eagle Aircraft Corporation capitalized on her fame by publishing an article about Ms. Kauffman in U.S. Air Services entitled “From Cold Cream Jars She Conjured Wings, And a Half-Pint Blonde Comes to Realize their Responsibilities.”

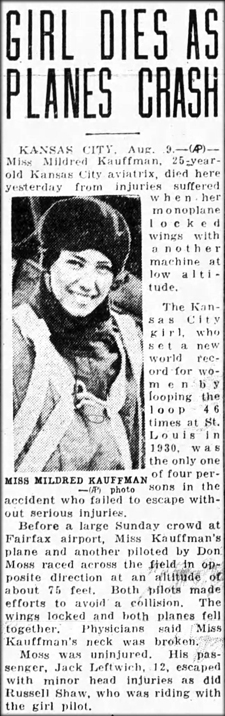

Back in her hometown of Kansas City in August 1932 before a large Sunday crowd while only 75 feet in the air, Ms. Kauffman collided with another plane. Both planes came down together, but of the four persons involved in the accident, only Ms. Kauffman suffered fatal injuries. At age 25 Ms. Kauffman would never get to fly the special plane constructed for her to compete at the upcoming National Air Races in Cleveland.

[1] A fully fueled Boeing 787-10 Dreamliner can fly about 8,000 miles with 300 passengers and their luggage (“Can Hydrogen Save Aviation’s Fuel Challenges? It’s Got a Way to Go” (NY Times, 2021))